4 ways to break the design process mold

At Catapult, we often don’t know what we’re doing.

That doesn’t mean we don’t have a clue, just that we frequently find ourselves doing things that haven’t been done before. At least not by our clients or us. But that is the hallmark of innovation – experimenting, exploring, pushing the boundaries of what we do and how we do it. And no place provides more fertile ground for the seeds of innovation than does design – creatively trying to solve a problem to achieve a specific goal. So how do we continue to push the boundaries?

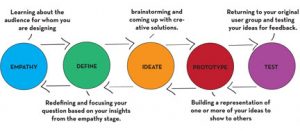

Design firms the world over tout their proprietary “design process” as a veritable secret sauce to innovation, treating their particular flavor of design thinking as a patented method replete with branded stages. This is understandable. After all, we are all just trying to differentiate ourselves. And to the uninitiated it works. But, if you were to take a quick survey of all the different design processes, they all follow the same general flow. Something that goes like: explore -> create -> produce.

image via www.mountvernonschool.org

And that’s all well and good. But there’s only so much innovation that can go on around the branding of a well-established process for tackling difficult challenges. Our feeling is that one of the areas in which designers can deeply innovate is not by simply following a tried-and-true process and repeatedly applying the same methods; but by also devising new methods and approaches to fit into the process.

The way is not always clear. In fact we’ve found that it looks different for nearly every client with which we work. And that is the bedrock of innovation – discerning what is called for in this instance – asking not what you’ve done before or what others are doing, but what this situation, right now, is calling for. And then doing it.

Here are four ways we’ve pushed our design process beyond the original, and traditional, model we adopted when we were just starting out. (Keep in mind that our work typically involves designing for end-users very far afield, both geographically and culturally.) Perhaps our readers are already building on these methods in their own practice?

1. Design mind-meld – Think of creative ways to integrate your expertise into the world of your clients.

Instead of doing your own independent research and preparing a report or delivering a prototype, insert a designer into your client’s team for an extended foray. By including a mind steeped in design thinking into their efforts to develop and implement a product, your client will be able to leverage the power of design much more broadly and deeply than they would have through a typical consulting agreement.

2. Extreme co-creation – Integrate the voice of the users into the products you design.

Co-creation has become a conventional talking point among design and innovation firms – as any quick search on the subject will show. If you can find these articles on co-creation in The Harvard Business Review, Forbes and Businessweek you know it’s mainstream. But instead of paying it lip-service, ask, how seriously involved can we get our end-users in the development of our product? Can we take prototypes to the field in order for them to provide feedback? Better yet, can we modify those prototypes in real-time based on their responses? Even better than that, can we create and modify prototypes in concert with our end-users there in the local context? Can we include them in our concept generation as active, not just passive, participants? Can they be a key component of our iterative design->test->design->test cycle?

3. Design destabilization – Consider how to challenge the assumptions that underpin design directions.

Sometimes the best way of serving a client is not to do what they request, but to instead ask them hard questions and suggest possible options that aren’t necessarily in keeping with their original direction. Such questions or suggestions can dramatically change the course of a project or even lead to it being cancelled altogether (clearly not your desire). This can be intimidating, and should not be done lightly or without serious thought, but it is central to the integrity of your designs and for looking out for your clients’ best interests.

4. User-originate design – Ask how to turn the whole process on its head; instead of user-centered design, how about user-originated design?

image via imusa.org

Here I am borrowing a phrase from Ralf Hotchkiss at Whirlwind Wheelchairs, where they are looking not to designers but to the users themselves for the inspiration behind their designs. This is stepping even beyond co-creation and is asking, “What if, instead of designing a wheelchair for disabled people, you instead taught them to design wheelchairs themselves and then supported them in doing so?” Can we remove our designers from the process altogether and let the users design their own products? Could they, perhaps, come up with better, more finely tuned, more considerate designs? This is a question Whirlwind is asking and, to me, is what innovation in design is all about.